Most people, after suffering consequences for a bad decision, will alter their future behavior to avoid a similar negative outcome. That's just common sense. But many social circles have that one friend who never seems to learn from those consequences, repeatedly self-sabotaging themselves with the same bad decisions. When it comes to especially destructive behaviors, like addictions, the consequences can be severe or downright tragic.

Why do they do this? Researchers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia, suggest that the core issue is that such people don't seem able to make a causal connection between their choices/behavior and the bad outcome, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature Communications Psychology. Nor are they able to integrate new knowledge into their decision-making process effectively to get better results. The results could lead to the development of new intervention strategies for gambling, drug, and alcohol addictions.

In 2023, UNSW neuroscientist Philip Jean-Richard Dit Bressel and colleagues designed an experimental video game to explore the issue of why certain people keep making the same bad choices despite suffering some form of punishment as a result. Participants played the interactive online game by clicking on one of two planets to "trade" with them; choosing the correct planet resulted in earning points.

For each click in two three-minute rounds, there was a 50 percent chance of choosing the correct planet and being rewarded with points. Then the researchers introduced a new element: clicking on one of the two planets would result in a pirate spaceship attacking 20 percent of the time and "stealing" one-fifth of a player's points. Selecting the other planet would result in a neutral spaceship 20 percent of the time, which did not attack or steal points.

The result was a very distinct split between those who figured out the game and stopped trading with the planet that produced the pirate spaceship, and those who did not. None of the participants enjoyed losing points to the attacking space pirates, but the researchers found that those who didn't change their playing strategy just couldn't make the connection between their behavior and the negative outcome.

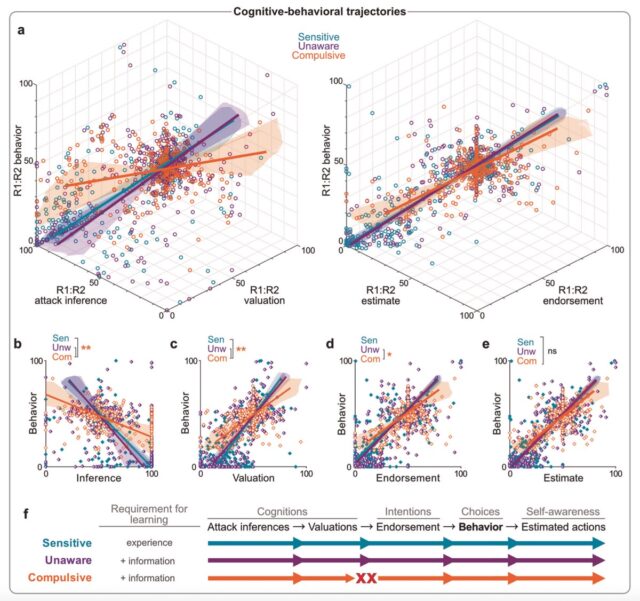

The team identified three distinct behavioral phenotypes as a result of their experiments, representing the varying sensitivity of people to the adverse consequences (punishment) of their actions. Sensitives easily make the connection between their choices and the outcomes and can adapt their behavior to gain rewards and avoid punishment. Those who fail to make the link are either Unawares—people who, once given further information or clues, can re-evaluate and change their behavior—and Compulsives, i.e., people who still persist in making bad decisions despite suffering consequences.

Expanding the pool

This latest study builds on that earlier work, using a variation of the same experimental online game: After a few rounds, the researchers told all the subjects which planet was linked to which ship and also which ship triggered the point losses. "We never directly tell them what the best strategy is; we just reveal how each action leads to particular cues and 'attack' (the point-loss outcome)," dit Bressel told Ars. "The reason being our studies have reliably shown all behavioral phenotypes, including Compulsives, are valuing cues and outcomes normally—and are totally aware of cue-attack relationships."

They also expanded the pool of participants beyond the Australian psychology students who were subjects in the 2023 study, sampling a general population from 24 countries of different ages, backgrounds, and experiences. And the researchers conducted six-month follow-ups in which subjects played the same game and were asked afterward whether they thought their choices and strategies were optimal.

The resulting phenotype breakdown was roughly similar to that of the 2023 study using just Australian students. About 26 percent were Sensitives, compared to 35 percent in the earlier study; 47 percent were Unawares, compared to 41 percent in 2023; and 27 percent were Compulsives, compared to 23 percent in the prior work. Those behavioral profiles remained unchanged even six months later. And the poor choices of the Compulsives could not be attributed simply to bad habits. The follow-up interviews showed that Compulsives were well aware of why they made their choices.

Cognitive-behavioral trajectories of behavioral phenotypes.

Credit:

L. Zeng et al., 2025

Cognitive-behavioral trajectories of behavioral phenotypes.

Credit:

L. Zeng et al., 2025

"The thing they seemed to specifically struggle with is seeing the link between their actions and its consequences," said dit Bressel. "Basically, lots of people (our Unaware and Compulsive phenotypes) don't readily learn how their actions are the problem. They fail to recognize their agency over things they are highly motivated to avoid. So we give them the piece of the puzzle they seemed to be missing. Correspondingly, simply telling people how their actions lead to negative outcomes completely changes the behavior of most poor avoiders (Unawares), but not all (Compulsives)."

The researchers admit it's a bit perplexing that so many Compulsives still persisted in making bad choices, even after receiving new information. Is it that Compulsives simply don't believe what the researchers have told them?

"There's maybe a little of that going on," said dit Bressel. "We ask them which actions they thought led to attacks and how they value each action, and they do strongly update their beliefs/valuations after the information reveal but not as much as the Unawares. So, Compulsives are a little less on board about the relative values of actions than other phenotypes. But we've shown this still doesn't fully account for how poorly they continue to avoid."

Better interventions needed

That's something the scientists are keen to explore further. "We showed Compulsives are very aware of how they're behaving, and also think their behavior is optimal—even though it really wasn't," said Jean-Richard Dit Bressel. "This suggested a key failure point is between recognizing the relative values of actions and forming a corresponding behavioral strategy."

Compulsives, in other words, exhibit deficits in cognitive-behavioral integration. "It's like they're thinking, 'Yeah, sure, Action A is good, Action B is bad... instead of a 50-50 split, I'll do 60-40,'" said Dit Bressel. "They really should be going cold turkey and doing 100-0. An implication of the trajectory analysis we did is that no amount of action belief updating would get them to behave optimally. We need a way to improve how those beliefs translate to perceptions of what's optimal."

What might be the underlying cause of this persistent bad decision-making? "We don't know, but the fact most people have the same profile at retest suggests this is a kind of trait: a stable cognitive-behavioral tendency," said Dit Bressel. "It could be related to genetics, but we don't have the data for that. We know there are environmental factors that contribute to the Compulsive profile: It's significantly more likely to emerge if the Action→Punisher relationship is infrequent, i.e., people will be poor avoiders and ignore helpful information if punishment probability is low, even if the punishment is severe. But this would be a case of trait-x-environment interactions. My neuroscientist side would love to explore what's going on in the brain and map what contributes to adaptive vs maladaptive decision-making."

This could help drive more effective public health messaging, which is typically focused on providing factual information about the risks of compulsive behaviors, whether we're talking about smoking, drinking, eating disorders, or gambling, for instance. The results of this study clearly demonstrate that for Compulsives, information is not sufficient to change their self-sabotaging behavior. One of Dit Bressel's lab members is now investigating better interventions for different profiles of decision-making, particularly for Compulsives.

"We definitely haven't cracked the case yet," said Dit Bressel. "There's a body of work that says early over late information intervention might do the trick, but we've shown Compulsives in low probability punishment scenarios are impervious to early information. If the issue is they can't infer the winning strategy with Action→Punisher, maybe explicitly outlining the winning strategy will make more of a difference. Or maybe some potent combination of prompts. We have ideas, but the proof will be in the pudding."

Then again, "It could be the case that no amount/type of information will be enough to really sway 'that friend,' and that something far more involved would be needed," he said. "But most people will have a least some response to helpful information, so my suggestion in the absence of a full answer is to just be a good friend and give that friend the info/advice they seem to need to hear (again). It won't go the distance for everyone, but it's cheap and you'd be surprised at how many people need what seems obvious pointed out to them."

Nature Communications Psychology, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s44271-025-00284-9 (About DOIs).